|

“This story of Dr. Alice Stewart, an audacious, insightful medical researcher, stands as a monument to the grit that allowed her to challenge tenets of mainstream scientific opinion.” —Stewart Udall, former Secretary of the Interior and author of The Myths of August: A Personal Exploration of Our Tragic Cold War Affair with the Atom “A vivid portrait of a much underestimated scientist who has been an indomitable challenger of the establishment and a thorn in the flesh of the nuclear industry.” —Joseph Roblat, physicist and Nobel Peace Prize winner, 1955 |

when“A spirited biography [of a] blunt, feisty woman’s career.”

--Publishers Weekly

“A fascinating mixture of biography and oral history. . . . Stewart’s scientific passion, her feistiness, her political naiveté and her wit shine in each chapter.”

—Women’s Review of Books

“For those who are intrigued by others’ life experience, this book has all the necessary ingredients: loyalty, love and a life that has been lived to the full. For those who relish the triumph of tenacity over adversity, this story illuminates the fight of those who believe that science may do harm as well as good and those who think that too rigid an application of regulation may stifle research which is contrary to received wisdom.”

—Medicine, Conflict and Survival

“An excellent account of [Alice Stewart’s] life and work and how the nuclear industrial complex has sought to marginalize her.”

—Voices from the Earth

“An informative and sympathetic portrait of the life of a rather unconventional and determined physician-scientist, whose world was shaped by the prejudices against women of an earlier day. . . . The real strength of this book lies . . . in its presentation of the trials and slights and obstructions and impediments placed in the path of a woman who dared to enter the male-dominated world of medical science in 20th-century Britain and the United States.”

--Nuclear News

“The Woman Who Knew Too Much seeks to trace Stewart’s unconventional approach in investigating the effects of man-made radiation. It provides some shrewd insights into her personality and methodology.”

—New York Times Book Review

“Greene enthusiastically chronicles Stewart’s fascinating family history . . . and demanding private life, and perspicaciously examines the ‘visions and doggedness’ that characterized Stewart’s pioneering and invaluable work. . . . Stewart’s story is one of perseverance, ingenuity, compassion, independence, and integrity, a noble tale in the checkered history of science.”

—Booklist

“Highlights the ways in which radiation risks have been defined politically and socially, and how the bearers of bad tidings have been marginalized by powerful vested interests, their research frustrated and their findings discredited.”

—Medical History

“An estimable book about the life of Alice Stewart and her role in the long, painful effort to understand and control the health effects of radiation.”

—Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists

“A sympathetic perspective about [Alice Stewart’s] long career, and about her role in the ongoing controversies about the carcinogenic risks of exposure to low-level ionising radiation.”

--Lancet

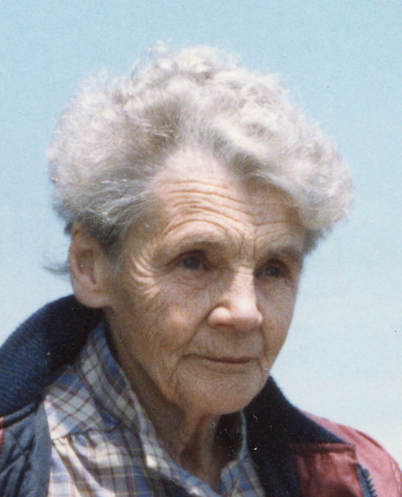

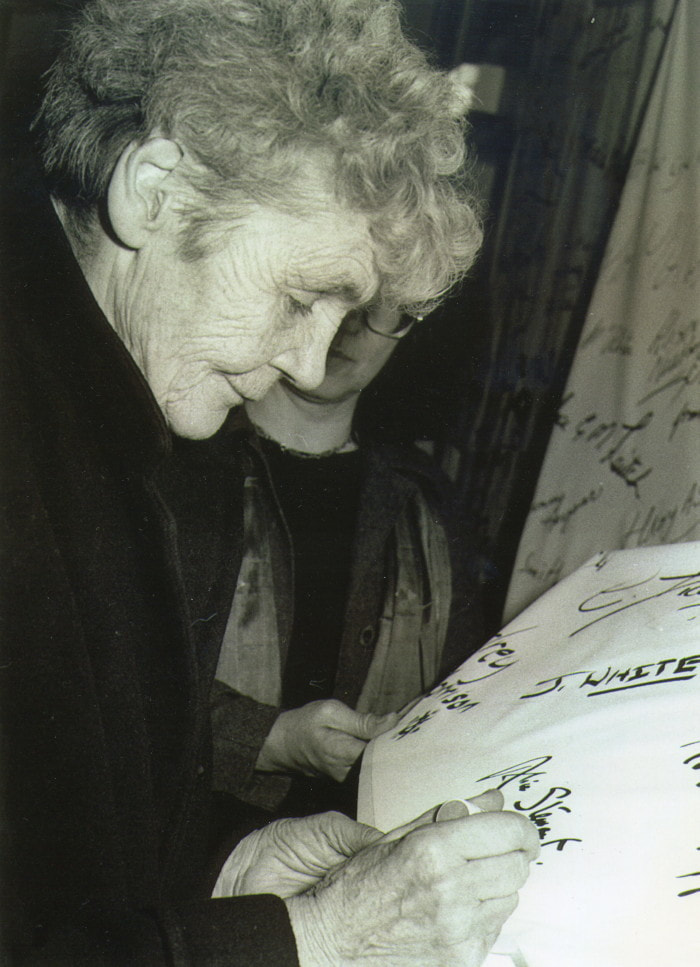

Alice Stewart is a world-class radiation epidemiologist who, in her seventies, took up the cause of radiation victims, nuclear workers and atomic bomb-test veterans, widows seeking compensation, children dying of cancer from radiation exposure, while the U.S. and U.K. governments claimed that radiation exposure played no part in this suffering. Stewart fought these battles in the courtroom, in Congressional hearings, in U.K. hearings about the siting of new nuclear facilities, in investigations of cancer clusters near facilities, and at anti-nuclear demonstrations throughout the world. She won a major victory in her mid eighties (1992) when she wrested the health records of U.S. nuclear workers from the stranglehold of the Department of Energy. She saw another triumph in her nineties (1999), when her research on nuclear workers won compensation for workers who developed cancer on the job. “It helps, in this field, to be long lived,” as she said.

In the 1950s, when her work turned up a link between fetal x-rays and childhood cancer, the nuclear arms race was raging, and the governments of the U.S. and U.K. were assuring the world that we could survive nuclear war by ducking and covering under school desks. Nobody wanted to hear that a tiny fraction of a radiation dose “known” to be safe could kill a child. For the unpopularity ofher findings, Stewart was defunded, defrocked, defamed. But she was that rare creature in science, an independent. Not beholden to government or industry for support, she could speak out.

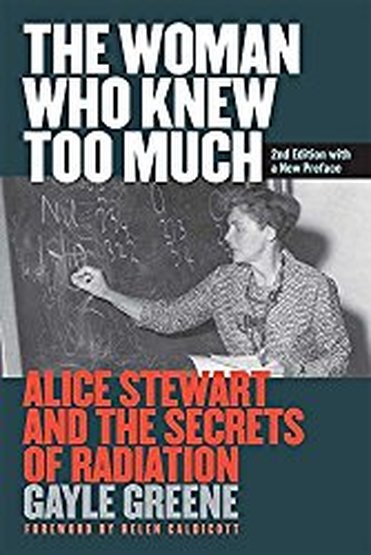

The Woman Who Knew Too Much was published in 1999 (University of Michigan Press, intro Helen Caldicott), when Alice was 92. It was never published in the U.K. because we said some unflattering things about Sir Richard Doll, a towering figure in cancer research who’d blocked Stewart's career from the get-go. She died in 2002, at the age of 95; Doll died a few years later, and in 2006, was discovered to have been accepting large sums of money from Monsanto even as he was using his considerable authority to exonerate Monsanto's dioxin of cancer risk. With this revelation (and others), the lines of a new story emerged, a tale of scientific rivals whose lives and work diverged radically, with Stewart plummeting to obscurity for her warnings about low-dose radiation risks, and Doll, skyrocketing to fame and a knighthood for downplaying those risks, issuing reassurances that governments and industry wanted to hear. This was another story I had to tell.

As the world watched the Fukushima reactors, in March 2011, spewing incalculable quantities of radionuclides into the sea and air and worried what effect this would have on our health and on generations to come, Alice’s warnings assumed a terrible timeliness. Industry, governments, and the media went into damage control, trying to quiet the alarms, assuring us that radioactive releases will dilute and disperse and disappear, invoking (yet again) the reassurances of Sir Richard Doll. Theirs was no mere academic disagreement; there are billions of dollars riding on this issue.

--Publishers Weekly

“A fascinating mixture of biography and oral history. . . . Stewart’s scientific passion, her feistiness, her political naiveté and her wit shine in each chapter.”

—Women’s Review of Books

“For those who are intrigued by others’ life experience, this book has all the necessary ingredients: loyalty, love and a life that has been lived to the full. For those who relish the triumph of tenacity over adversity, this story illuminates the fight of those who believe that science may do harm as well as good and those who think that too rigid an application of regulation may stifle research which is contrary to received wisdom.”

—Medicine, Conflict and Survival

“An excellent account of [Alice Stewart’s] life and work and how the nuclear industrial complex has sought to marginalize her.”

—Voices from the Earth

“An informative and sympathetic portrait of the life of a rather unconventional and determined physician-scientist, whose world was shaped by the prejudices against women of an earlier day. . . . The real strength of this book lies . . . in its presentation of the trials and slights and obstructions and impediments placed in the path of a woman who dared to enter the male-dominated world of medical science in 20th-century Britain and the United States.”

--Nuclear News

“The Woman Who Knew Too Much seeks to trace Stewart’s unconventional approach in investigating the effects of man-made radiation. It provides some shrewd insights into her personality and methodology.”

—New York Times Book Review

“Greene enthusiastically chronicles Stewart’s fascinating family history . . . and demanding private life, and perspicaciously examines the ‘visions and doggedness’ that characterized Stewart’s pioneering and invaluable work. . . . Stewart’s story is one of perseverance, ingenuity, compassion, independence, and integrity, a noble tale in the checkered history of science.”

—Booklist

“Highlights the ways in which radiation risks have been defined politically and socially, and how the bearers of bad tidings have been marginalized by powerful vested interests, their research frustrated and their findings discredited.”

—Medical History

“An estimable book about the life of Alice Stewart and her role in the long, painful effort to understand and control the health effects of radiation.”

—Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists

“A sympathetic perspective about [Alice Stewart’s] long career, and about her role in the ongoing controversies about the carcinogenic risks of exposure to low-level ionising radiation.”

--Lancet

Alice Stewart is a world-class radiation epidemiologist who, in her seventies, took up the cause of radiation victims, nuclear workers and atomic bomb-test veterans, widows seeking compensation, children dying of cancer from radiation exposure, while the U.S. and U.K. governments claimed that radiation exposure played no part in this suffering. Stewart fought these battles in the courtroom, in Congressional hearings, in U.K. hearings about the siting of new nuclear facilities, in investigations of cancer clusters near facilities, and at anti-nuclear demonstrations throughout the world. She won a major victory in her mid eighties (1992) when she wrested the health records of U.S. nuclear workers from the stranglehold of the Department of Energy. She saw another triumph in her nineties (1999), when her research on nuclear workers won compensation for workers who developed cancer on the job. “It helps, in this field, to be long lived,” as she said.

In the 1950s, when her work turned up a link between fetal x-rays and childhood cancer, the nuclear arms race was raging, and the governments of the U.S. and U.K. were assuring the world that we could survive nuclear war by ducking and covering under school desks. Nobody wanted to hear that a tiny fraction of a radiation dose “known” to be safe could kill a child. For the unpopularity ofher findings, Stewart was defunded, defrocked, defamed. But she was that rare creature in science, an independent. Not beholden to government or industry for support, she could speak out.

The Woman Who Knew Too Much was published in 1999 (University of Michigan Press, intro Helen Caldicott), when Alice was 92. It was never published in the U.K. because we said some unflattering things about Sir Richard Doll, a towering figure in cancer research who’d blocked Stewart's career from the get-go. She died in 2002, at the age of 95; Doll died a few years later, and in 2006, was discovered to have been accepting large sums of money from Monsanto even as he was using his considerable authority to exonerate Monsanto's dioxin of cancer risk. With this revelation (and others), the lines of a new story emerged, a tale of scientific rivals whose lives and work diverged radically, with Stewart plummeting to obscurity for her warnings about low-dose radiation risks, and Doll, skyrocketing to fame and a knighthood for downplaying those risks, issuing reassurances that governments and industry wanted to hear. This was another story I had to tell.

As the world watched the Fukushima reactors, in March 2011, spewing incalculable quantities of radionuclides into the sea and air and worried what effect this would have on our health and on generations to come, Alice’s warnings assumed a terrible timeliness. Industry, governments, and the media went into damage control, trying to quiet the alarms, assuring us that radioactive releases will dilute and disperse and disappear, invoking (yet again) the reassurances of Sir Richard Doll. Theirs was no mere academic disagreement; there are billions of dollars riding on this issue.

|

Parts of this story went into a second edition of The Woman Who Knew Too Much, 2016. A longer version is in an article, “Richard Doll and Alice Stewart: Reputation and the Making of Scientific Truth,” Perspectives in Biology and Medicine, Autumn 2011 (reprinted in Women and Gender in Science and Technology, ed Londa Schiebinger, Routledge, March 2014; also in Corporate Ties that Bind: An Examination of Corporate Manipulation and Vested Interest in Public Health, ed. Martin Walker, Skyhorse Publ, 2016)

See below for the LINK to this article. |

|

Here’s a blog that went viral:

“The Nuclear Power Industry After Chernobyl and Fukushima” Here are some videos: Me, reading the first pages of the book British Medical Journal feature on Alice Stewart A TED talk by Margaret Haffernen Here's my article “Richard Doll and Alice Stewart: Reputation and the Making of Scientific Truth” in Perspectives in Biology and Medicine, Autumn 2011 (reprinted in Women and Gender in Science and Technology, ed Londa Schiebinger, Routledge, March 2014, and in Corporate Ties that Bind: An Examination of Corporate Manipulation and Vested Interest in Public Health, ed. Martin Walker, Skyhorse Publ, 2016)

Here are full reviews of The Woman Who Knew Too Much from Publisher's Weekly, JAMA, Nature, Lancet, Bulletin of Atomic Scientists, New York Times, and others.

| |||||||||||||